FIELD NOTES / 05

20 FEET CLOSER TO GOD - Extended Version

(Shortened version published in Traditional Bowhunter [Feb/Mar 20.])

By Andri Elko

Photo by Chris Chastain.

“When a hunter is in a tree stand with high moral values and with the proper hunting ethics and richer for the experience, that hunter is 20 feet closer to God.” — Fred Bear

The simple and subtle qualities of traditional archery allow us to enter the unknown lightly, quietly, and humbly. Our accuracy is reliant on discipline alone. Our ability is honed through repetition and the practice of discernment. Ideally, with every full-draw, we are drawn deeper into ourselves.

Every instinctive archer understands this. We don’t think about when to release an arrow, it just happens when everything feels in alignment. And if you touch upon that alignment with truth when you release the arrow, then there is an alignment with truth in where the arrow finds center. Our guidance rises from a foundry deeper than that of thought. Like a compass, each decision and every response operates under the influence of unseen forces. At that ancient precipice that precedes a loosed arrow, we connect to a place that can only be understood through direct experience; and it feels like a sacred place.

—

Traditional archery invites you closer. It involves a kind of intimacy that has been slowly eroding beneath waves of hunting technology and long-range tactics. Bowhunters learn to tread the earth more lightly. We hunt for experiences, not for exchanges. We tap into subtle degrees of awareness; we practice the art of patience, we let go of expectation, and we refrain from getting in our own way. Our hunt becomes a kind of communion, an interplay between the earth and our short walk upon it — a conversation between our better selves and that which is always learning and growing. Traditional archery is timeless. And all that is timeless can also be a catalyst toward the deep eternity within our souls, and it is there that we begin to truly know ourselves.

After a lifetime of rifle hunting, and a bit of compound time, I felt a deeply seated desire to simplify, to rely less on commercial gear and more on my own instinctive ability. I wanted to get up close and personal; both literally and figuratively; both with the outer wilderness and with the wilderness within.

So, I decided to build a bow.

—

I called the nearest bowyer. With a guarded response, he said that he couldn’t show me his workshop or share any of his bowyer know-how because it was his livelihood. I understood that inclination, but I also believe that when we don’t share knowledge and art, we all lose. Traditions and traditional knowledge are inherently meant to be shared and passed on. This is part of traditional archery’s ancient beauty; and this is precisely why we are able to partake in that beauty today.

Thankfully, as fate would have it, I found a local bowyer though TradGang. Brad’s generosity in teaching me what he knows about traditional archery has been a blessing in my life; as has his friendship. I’ve learned as much about bowery and traditional archery as I have about attitude, character and values that truly endure all things. I’ve been welcomed into a community of archery hunters; a community that is rich with experience and wisdom gained through years of trial, error, and grit. We’ve shared stories, shared knowledge, shared hot-wings and beer. We’ve shared the joys of our successes. We’ve also shared the swell of encouragement that fills up the wide stretch between every peak of success.

Our traditional hunting community is much like a bow. Alone, a bow is just a piece of wood. Its purpose is limited without its relationship to the tight string, the arrow, the aim, and the archer. Without the relationships we cultivate, we too are alone and limited. I’ve learned that the traditional community is a tight community that can bring people together, achieve shared aims and purposes, and encourage us to participate collectively while also allowing a reserved place for our individuality. The traditional bowhunting community feels like a treasure unearthed; and in finding it, I’ve also found a part of myself.

As hunters, it seems that our choice of weapon mirrors aspects of who we are. As we distill and simplify, we lessen the weight and clutter, which in turn gains us a clearer glimpse of our identity within this human experience.

What does it mean to be a hunter?

What does it mean to be a good hunter?

Ultimately it is not a bow or rifle that makes someone a good hunter. It’s not the gear or number of years put in. It’s the heart that makes us hunters. When our hearts are in alignment; the aim will be true.

This is what I’ve learned from my experiences, from family, from Brad, from other bowhunters, from time in a tree that lifts me 20 feet closer to God. I am forever grateful to the people who have accompanied me along this seeker’s path. That’s the thing about uncovering truths: when they’re unwrapped, they can be applied to all of life. In this way, traditional archery has evolved from an activity and a pursuit into a kind of philosophy, a lens through which to see the world in which we live.

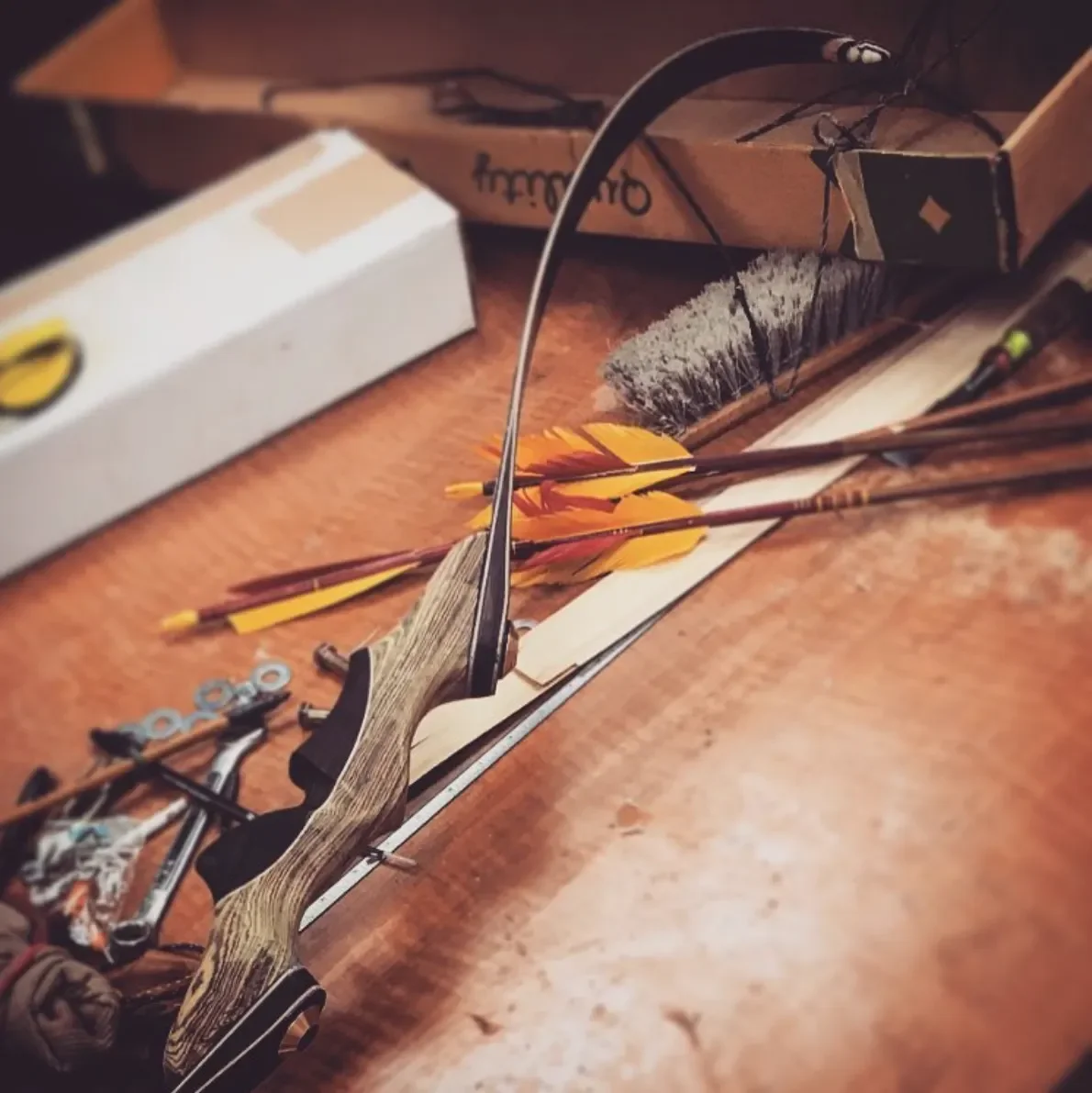

My first self-made bow, pictured just prior to the last stage of a finish application. It’s a take-down recurve with an ebony/bacote riser, maple accents and black fiber-glass limbs. Photo by Andri Elko.

—

The first bow that Brad and I built together was a three-piece take-down recurve. I love that bow. It’s beautiful. Hours were spent in the shop and at the sander. We wanted to make it as minimal as possible without compromising strength and function. If we didn’t need any material in a particular area, we sanded it away. Bare minimum was our motto. The result was elegant, simple and inviting.

I could never have dreamed up a better first bow. It came in a bit under our target draw-weight, but it’s lovely in the grip and makes for a smooth shooting small-game and target bow. Having made it, having watched it come to life, I can see how the qualities that have been poured into making that bow now accompany me everywhere I carry it. It holds good vibes of friendship; it keeps alive the memories of shared knowledge and determined efforts; and it reflects the gratitude that grew with it and continues to grow with every draw of its twisted string. Even when I go out alone, with that first self-made bow in my hands, it feels like I have an old friend by my side.

A few months (and a few bows) later, Brad introduced me to his buddy Chad, of Holm-Made Traditional Bows. Brad, Chad, Chad’s son and I played wack-a-mole in the prairie dog fields during daylight hours. In the evenings, the guys helped me build a longbow in Brad’s shop.

I found pecky pecan veneers that looked stunning under glass. We stacked contrast accent wood on the belly and back of the riser; creating a look that is almost topographical in how the layers accentuate the contours of the bow.

At a 40-plus pound draw-weight, this is the bow I took to the woods that fall. It’s light and quiet. It practically disappears into Dakota’s golden prairie grass. Someday I want to nock it with flu-flus and go after pheasants. But for now, it’s set up for deer. I strapped a Selway quiver on the limbs and filled it with the cedar arrows that Chad had so generously sent me from the Footed Shaft.

To me, hunting is 5% opportunity, 5% skill, and 90% relationships. The success of one person is always, to some greater or lesser degree, a shared success. Relationships craft and cultivate our perceptions, fortitude, ethics, and our memories. We learn from Nature and from one another. What we take away from our experiences becomes part of the story we leave behind.

Stretching a flemish-twist string with Alaskan beaver-fur silencers. Photo by Andri Elko.

Chad Holm teaching Andri how to make a longbow. Photo by Brad Davis.

Cedar shafts and turkey feather fletchings. Photo by Andri Elko.

—

I set my goals.

I fortified my foundation.

I built my longbow.

Now, it was time to buy tags and take to the woods.

One brisk fall morning Brad took our friend Natashia and me to his stands in the Badlands. We scurried through a field, crossed a shallow river, and climbed up into the trees. I settled in just as first-light began to crawl across the ancient strata of a land that’s been hunted since the dawn of time.

I liked this setup. The old juniper wrapped around me. I felt like an owl sunken into a hollow; and like an owl, there I sat, camouflaged into a grayish-brown background of bark.

In the last 10 minutes of my sit, a large doe emerged out of the foreground. She came forward like a wisp of smoke. Silently, she walked into a widened corridor about 15 yards from the stand. I drew 3/4 of my full draw, my mind turning back and forth about the shot, and then I let down.

I wrestled with the idea of shooting this doe because I had set my heart on a buck. It was a clear shot, but something I can’t quite articulate kept me from taking the shot.

She tip-toed in a little closer. She stood broadside. She turned her head and stared back into the timber. Her right front leg extended out in front of her, and I could see that tuft of snow-white fur beneath her armpit. It was almost like she was inviting me to shoot, waiting on me. I drew back again, held for a second and let back down.

Everything was picture-perfect for a clean shot. Externally, all signs were a “go,” but everything inside me said, “Wait…wait…this isn’t the right deer, this isn’t the right moment.” As much as my practical mind rationalized this excellent opportunity, I could not ignore what I was hearing within. I knew that if I let that arrow loose, I would be doing it for the sole purpose of shooting a deer. This would have been fine if it were how I had set out from the start. But, it would have been a betrayal to myself if I had not listened to that inner guidance. After all, this is why I set forth down this traditional path in the first place — to tap into that something deeper.

—

My Dad’s friend, Chip, let us hunt near a North Dakota river bottom. It was nice to be in the woods with my Dad again. We set up in a ground blind as darkness quietly lifted. The land was alit with that old familiar cold-blue hue. Deer criss-crossed through the trees in the distance, but no bucks came within bow-range.

For the evening sit, Dad and Chip and I thought it would be best to go sit in the treestand. They dropped me off at the stand and went back to camp to wait. This was my last sit of the season, and we all were keeping our hopes high.

I’d been up the tree for several hours without a deer in sight. The sun was sinking now, and I knew there was only an hour or so of shooting light left. I was starting to feel the chill so I did some slow deep breaths and imagined my body warming up with every exhale. Hunting, as so many of us know, is often a challenging exercise in mind over matter.

Then, in a blink, things started to change.

A doe and her two young ones walked beneath my tree, following one another along their heavy trodden path from the timber line. They lingered under the shadow of my tree for a while. Then a buck sauntered in, circling the doe below. He had only one antler left. It was broken off into a ragged spike. I mentally hemmed and hawed about that buck, thinking,“This is a buck after all, and this is the last hour of my season.” But still there was that inner voice telling me to wait. Let me clarify here that I was not being choosy, although to some it may seem that way.

I was listening in.

I entered that sacred space.

I waited.

Then, minutes before the ember of last-light began to fade, the magic began to stir…

Hearing the crunch of hoofed-steps in the snow behind me, I stilled myself, slowly peered over my right shoulder, and saw a mess of antler directly below me. I counted up to five points and quit counting. I quit looking at the antlers all together. In a flash and without a doubt, I knew that this was a great buck, and one that far exceeded any hopes I might have had.

Maybe 20 minutes of shooting light remained now. The doe and her two fawns were still out in front of me. This buck stopped 12-yards out and quartered away a little. I drew back, but one of the young ones spotted me and spooked, which caused the buck to spook too. He shuffled a little, and his eyes seemed to grow in size. I let down a little and froze.

Time stretched.

The deer grew calm and comfortable again and scattered around my tree. This was difficult to contend with, because no matter how you draw back, the odds are that at least one eye is going to catch your slightest movement. The buck was still in the 10–12-yard range. He nosed the ground there, maybe catching wind of doe scent.

I pulled back on my string, and at partial draw the buck grew suspicious again. I froze. Then the buck turned his head just enough for an antler to cover his right eye, and there it was: the window.

It is in those seconds that stretch time — when too much time can miss the opportunity altogether and too little time can ruin the opportunity by rushing it — that we find ourselves at a threshold that leads us into something deeper. For some of us, our minds quickly make the decision for us. But there are those of us who listen in and enter. From this threshold it feels as though some force — both beyond us and at once within us — takes the helm. We watch things unfold naturally, in the same harmony and balance shared by all other forms of Nature that unfold in sync with their primordial pace and rhythm.

I finished into a full draw, anchored, and that arrow took flight like it knew where it was going. I watched the feathered fletchings indicate a solid shot. The buck spun and bolted. I can still picture him leaping in the air with my fletchings barely sticking out of his right side. I didn’t get visible full penetration of the arrow, but it must have been partially through the other side because the deer’s movement worked the arrow through and through, and I never recovered it.

The shot-angle was ideal.

Both lungs were hit; it was clean and lethal.

Practice shots 20 feet up. Photo by Chip Erickson.

North Dakota whitetail. Longbow. 2018. Photo by Vance Grishkowsky.

North Dakota whitetail. Longbow. 2018. Photo by Vance Grishkowsky.

—

A hunt can often be distilled into one vital moment. But that moment is never truly lived without first giving it the time that it calls for. Time, as such, becomes a quiet teacher. There are things in life that cannot be rushed; things that swallow up time and nourish us with an accumulation of gifted moments. We fill ourselves with these fleeting gifts which feed a hunger, a yearning, within us. Every moment becomes a bread crumb leading us closer to, and further into, that something deeper we all seek, whether we are aware of it or not. As we dwell in those depths, we begin to understand what timelessness truly entails.

Outwardly, I am gifted with a beautiful harvest: clean wild food in the freezer and an exceptional memory of shared experience.

Inwardly, I am fulfilled in ways perhaps only revealed to those who tread the wild unknown. We wait in the cold brittle air of a late fall season. We struggle in our quest to cast out any excess of thought that clutters up an expectant mind. We reach inward for that ancient alignment, trying to find our way into the depths of that timeless space. To touch upon that timelessness just once, is to touch upon it forever.

We sit there alone in the stillness and the silence. Some part of us clings to a primal human memory, one that remains safeguarded in the vault we each carry within. We cannot force our way into that vault; only stillness, silence and surrender can show us the way in.

And even when we appear to stand alone; even when the judgements of others isolate our actions — still, we all together share that upwelling sense of gratitude that visits in moments of blessed unfolding.

Just as we admire a fiery sunset, so too, can we appreciate a clean and pure hunt. To know, in that deep inner reservoir, that all life lives on, unbound by time and earthly form. We find our way into a sacred connection, one that unveils and hones the edge of our ability to discern that great yet subtle difference between taking and receiving.

To date, I’ve only harvested this one big game animal with a traditional bow setup. In terms of tags and years, I can’t claim to be an expert to any reasonable degree. But traditional archery seems to me to be a qualitative venture, not a quantitative one — one that truly does lift us 20 feet closer to God.

What I felt with one well-placed arrow is perhaps the truest aim of today’s take on traditional archery. And for the gift of that moment — for that flicker of pure immersion into the ephemeral borderlands of our human experience — I am grateful.

“The history of the bow and arrow is the history of mankind.” — Fred Bear

“All America lies at the end of the wilderness road, and our past is not a dead past, but still lives in us. Our forefathers had civilization inside themselves, the wild outside. We live in the civilization they created, but within us the wilderness still lingers. What they dreamed, we live, and what they lived, we dream.” — Thomas K. Whipple

FIELD NOTES / 04

IF STORY WERE TANGIBLE

By Andri Elko

I love a beautiful knife. A Damascus blade. A burnished leather-stacked handle. Stabilized mammoth scales. Brass rivets and bolsters. Japanese chef knives. Finnish outdoor knives. A pocketknife bearing the marks of hard-earned wear.

There’s also just something extra special in a knife that’s been passed through generations. It feels heavy with story and experience when you hold it, almost like an artifact.

I won’t even start in on blade shapes and grinds and cultural influences. This world of ours has cultivated a kaleidoscope of beautiful attributes, components, mechanisms, materials, advancements and histories regarding cutting tools. I am not a blade expert by any means, but I do appreciate the crafting that goes into a well-made blade. Some are functional art, and others are simply functional. And if story were tangible, manual tools — like knives — become storytellers.

Flintknapped arrowheads come to mind. Or a grandparent’s rusted and aged (and probably initial-engraved) handsaw. Sometimes you find things at garage sales, thrift stores and pawn shops that just look like they once belonged to someone who held onto things a little longer than we tend to these days. It paints a picture in your mind of someone who had one good set of tools, who used that same set of tools for decades, if not longer. The kind of person who wears a knife on their leather belt, so routine that it’s almost a part of them — like wearing glasses or a wedding ring. They probably kept a toothpick in a shirt pocket too, like all the good ol’ cowboys do.

Our generation might not have that so much. We’re part of a consumer generation that’s fueled by built-in obsolescence and the shiny lure of newer and better.

I’m trying to harken back more, whittle down the excess, save what has both inherent simplicity and endurance, when I can. It’s not easy, but shucks, it sure seems like it should be.

So I try to buy and/or save based on materials that get better with time — which is almost always something that is only a few steps away from its origin e.g. leather, fur, wood, stone, clay, glass, metals and natural fibers. These materials feel more connected and real in some way, unlike plastics and other synthetics. But they also usually require more care — maybe that’s part of why we hold onto them longer.

There can be beauty in synthetic materials too. I‘ve seen that beauty revealed when discarded synthetic materials get repurposed into something new. I saw this in South African markets, where colorful plastic-sheathed telephone wire had been woven into extraordinary basketry. The world is full of this creative repurposing. It’s almost like a modern-day morphing of hunting, gathering, and harvesting.

Most recently, I saw this in beautiful bags called kalzngaq that a pastor friend used as an example of new-life in a sermon that he gave. These woven bags are gorgeous. Their Cup’ig makers walk the beach gathering strands of fishing-rope debris along the shores of Mekoryuk. They then weave them, one salvaged strand by one salvaged strand.

The result is an object of use — a utility bag. But it’s also so much more than that. It’s art, it’s love and care; it’s resourcefulness, resilience, and redemption. It’s beautiful. And it is tangible story that can be crafted, held and shared — and maybe even passed down.

All romanticism aside, and in getting back to cutting-tools — it’s hard to beat an efficient and affordable work horse. For our family, this is the RADA Stubby Butcher.

Here are some of its specs from the RADA website:

Blade length: 5 3/8"

Overall Length: 9 7/8"

Blade Steel: Surgical-Quality, T420 High-Carbon Stainless Steel

Handle material: Comes in options of Aluminum or Black Resin

Production: USA

Bonus: Comes with RADA’s Lifetime Guarantee

This knife is a do-all knife. I can fillet salmon with it, skin a beaver with it, chop veggies with it and slice my steak dinner with it. And, just as importantly — I can put an edge on it quickly with RADA’s awesome Quick Edge Knife Sharpener.

We use this knife for everything! Seriously.

I was packing my RADA knife and sharpener before heading up the river the other day, and it got me to thinking two things:

I was thinking how I wish RADA made a sheath for this knife.

I was thinking of ways to give this family-favorite a little extra love.

I can’t do anything about my first thought, except continue to find and make sheaths. I’ve made them from cardboard and tape when I needed something fast. Currently, I use a repurposed Rapala sheath that works very nicely. I’d like to make my own custom leather sheath someday, but haven’t gotten to that project yet.

For my second thought, I went into the shop.

From there, I grabbed a spool of marine fishing twine that is usually used for mending herring nets. This nylon cord is minimal, yet hardcore. It can handle a beating. Also, the ends can be melted with a lighter to avoid fray.

My hope is that this twine will offer some grip to my RADA Stubby Butcher handle. The added plus is that it also offers a subtle wink and tip-of-the-hat to our hometown fishing culture. I only wish I could have found the cool sea-green colored twine that we used to have on hand — I love that color.

This twine that I’m using today is just basic white. Well, maybe off-white now, because it’s old and tinted with time, dust and maybe a little garage grime. I suspect paracord would work well too, it’s a common knife handle material. I just don’t have any on-hand at the moment. Leather cord would be awesome, but again, none on-hand. So, old fishing twine it is!

I tried a few different whippings and wraps, but the best one I‘ve come to settle on is the wrapping method used for serving on a bowstring. This technique came out the best in terms of being the most uniform, tightest and comfortable to grip. It actually feels really delightful in my hand; the parallel wraps have a clean and cohesive texture. Aesthetically, it has hints of minimalist Japanese knife design elements.

This bow-serving method was also the easiest and safest to perform in comparison to the others that I tried on this fixed blade handle. It will also be quick and easy to replace when/if needed.

As for sharpening.

I tested the RADA Quick Edge Knife Sharpener on one knife’s edge. Then I tested the sharpener previously mentioned in Field Notes 03 on another knife’s edge.

The result: RADA put on a sharper (and quicker) edge.

So, I did another test using the RADA sharpener on my broadheads. It won that round too. It was easy to sharpen on the arrow. The edges were subtly sharper than the ones sharpened on a stone with oil. It’s hard to beat a better edge result that can be achieved quickly without the need for oil or a cloth or an angle-jig to do it.

(Keep in mind these are not single-bevel broadheads, these are double-bevels.)

The most satisfying part is that it looks like I‘ve finally found THE sharpener, THE ONE that feels perfect for (almost) every situation. The one I was still looking for last week back in Field Notes 03. And the crazy part is, I’ve been using this sharpener on knives for years, YEARS! And only now did I try it on broadheads.

I guess sometimes our common sense gets swayed and obscured by thoughts of “this tool is for this and that tool is for that.” But some tools, it appears, are good for both this and that. And that’s what we find with the RADA sharpener.

Maybe there’s something to be said in using what’s around and readily available. Maybe there’s something to be said in following the examples quietly set forth by people living closer to a less-cluttered past. I’ve come to see that there’s beauty in simplicity. There’s value in repurposing and multi-purposing. And there’s something to be admired in doing more with less.

FIELD NOTES / 03

I LIKE SHARPENING

By Andri Elko

Maintaining sharp broadheads is important. Especially with traditional archery, where our draw weight and arrow speeds tend to be lower in comparison to most contemporary compound bows.

Traditional archery, ideally, takes place inside of 20 yards. Some archers can stretch that out to 25-30 yards with a lot of practice and proper equipment. Close proximity is crucial for ethics and respect when taking the life of a wild animal using traditional methods. All equipment has inherent limitations. With traditional archery, those limitations can be curtailed with measures of well-suited and well-maintained equipment and also with arrow release only when within the archer’s capable range.

Tradbow hunters tend to love close proximity. It feels like you’re immersed in Nature, a silent spectator, privy to a secret world. Extra challenge comes with it, too, in making yourself invisible enough to bear witness; to watch without being watched; to see and hear what few humans these days venture to see and hear.

These kinds of close encounters evoke a rare intimacy. There’s both adrenaline and peace; both over-thinking and meditation; both practicality and poetry. These dichotomies of human experience are all wrapped up simultaneously. We discover them in a good sit, or in a day well-spent glassing prior to a stealthy spot and stalk. They’re revealed in moments: in the fleeting colors of a sunset that prelude the end of shooting-light; in the fresh scent of sweetgrass that lingers in heavy evening air; in the birdsong that “plays” in the background while walking through timbers and prairie fields. They are found, also, in the effort behind every well-placed arrow.

With a tradbow, there isn’t an optic to look through like we have with rifle hunting. Nothing on the bow is going to make your target appear closer. There’s no gauging where to shoot based on a peep and a pin. There is no added component to help compensate for human error or shortcoming. But there is something, something pure and primitive in being close enough to share space with what you’re aiming at; in being close enough to pick a specific vital spot for the most clean and ethical aim.

When I’ve shot compound bows in the past, I didn’t bother much with sharpening broadheads. I could easily just replace them entirely by screwing in a brand new razor-sharp-out-of-the-box identically machined broadhead. Or, I could replace blade inserts for a brand new razor sharp edge. With traditional archery, though, broadheads are glued on, kept longer, and they usually don’t have mechanical or replacable parts. Broadheads that are designed for the tapered end of wooden arrow shafts typically need to be sharpened often — especially in preparation for a hunt.

I like sharpening; the sound of the burrs and rough edges grinding away on the sharpening plate or stone. Fine metal residue gradually turning the oil from clear to gray, then to charcoal-black — evidence of making headway.

Sharpening with oil is convenient too, because I can use that same oil for the steel maintenance of my broadheads after sharpening them. Broadheads designed for wooden arrow shafts are often made of high carbon steels. This kind of steel needs oiling from time to time to help prevent rust.

I have yet to find the sharpener, the one that feels perfect for every situation. I’m still exploring different sharpening products. I figure it’s good to have something for a workbench and also have something else that’s packable and will get the job done quickly in the field. It’s even better if that field sharpener is lightweight and can sharpen various edges.

For today’s sharpening, I used a recently purchased OZCUT 2 Easy Broadhead Sharpener. It has 1000-grit diamond plates set at 30-degrees on one side. Per the product description, this is designed to accommodate edge angles on both two and four-blade broadheads. On the opposite side of those angled plates, we find a single flat plate. The flat plate is designed for sharpening three-blade broadheads and straight blades, like a hunting knife.

This sharpener is robust, and feels solid and reliable. It’s a hefty piece of machined metal. Both sides seat firmly on a flat surface. I only wish they made the two hollowed-out tunnels in the main brick functional as storage for a small re-fillable bottle of oil on one side, and maybe a wiping cloth on the other. That way, I’d have all I need for the task in one handy all-in-one package.

Another thought is that many broadheads are not sharpened to a 30-degree angle. There’s a lot of online talk about edge angle, and about finding that perfect combination of cutting quality and durability. For single bevels, you’d still need to use a jig on the flat plate side with this sharpener.

For my broadheads, I tried both sides, just to test things out. In a perfect world, I would have loved the option to adjust the plate angles and their proximity to one another. But that isn’t an option with this product. So, I tried running one broadhead at the 30-degrees. Soon, I had to modify my approach because I was unable to grind the full edge as the tip of my broadhead sat in the channel with no grind. I then tried free-handing my grinds on the flat-side with a shallower angle and that allowed me to grind the full edge. But that came at the cost of using the angled side, which was part of why I purchased this.

I was hoping this would be a quicker tool than using a jig. I wanted something that could put a fast edge on my broadheads while they’re on the arrow. I wanted something for quick and easy touch-ups. I can’t say that the outcome I got is perfect, but I am pleased with how quickly I was able to obtain a sharp edge with this setup.

I think some of the design elements that required me to modify my technique could be remedied. I’ll explain a little, because I think it can lead to customer awareness and maybe even improvements in the design.

As I noted before, this sharpener is designed with a center channel. This channel accommodates the extra axis of 4-blade broadhead shapes. It’s advertised as a sharpener for any broadhead, not just the company’s broadheads. My issue with that channel is that it results in the plates missing the apex of my ACE Standards, so I found myself needing to manually adjust for that. I’m sure it’ll be great for my compound setup, but it’s not currently meeting the needs of my traditional setup in the ways that I desire.

From a design standpoint, I think the channel issue could be remedied with an easy modification by designing the angled plates to slide toward center where they could then be tightened down into place with the existing inset screws. This could be achieved by replacing the single screws on each end of the plate with either an inset slide-groove, or — even simpler — by offsetting the current screw insets on each end. This way, the user could simply remove the screws, flip the plate orientation, and tighten it back into place. As a result, the user could choose to have the plates touch on center or choose to leave the channel open for other broadhead styles.

That’s just my own two-cents on getting more out of the existing design. I’d probably also include a small hex or phillips tool for the screws, and I’d mill a storage-slot into the main brick for storing that tool. I love when tools are stored in the product that needs them! It’s efficient, and thoughtful.

Additionally, there’s potential for a cut on price-point that could be achieved by reducing the packaging that went into this sharpener. Ideally, packaging should be practical, minimal and maybe even useful. Great packaging is all of that, with the added plus of being artful or playful.

This sharpener, on the other hand, came housed in an elaborate box that included elements of paper, plastic, magnets, metal and foam. Inside the box was a hard plastic housing for the sharpener. The housing was framed with LED strips on two sides. On the backside, wires connected the LED strips to a compartment with 2 AAA batteries. The batteries were corroded and not working at the time that I purchased it. This also meant that the LED’s were not working at the time of purchase either. And, on top of all that, why would I need a hard plastic protection housing for something that’s built to withstand wear and tear? Honestly, the excess and the LED’s do not impress me. But the performance and the results from this product do.

Sometimes, less really is more, and more is just overkill.

All-in-all, I’m happy with this purchase. It’s a great sharpening tool for fast and sharp results. Albeit, it’s probably better suited for my compound broadheads than my for traditional broadheads.

I asked my Dad for his pocket knife. We both tested its initial sharpness. It was fairly dull from use. In less than 5 minutes I had a new edge on it for him. It took no time at all to get the sharpener, apply the oil, run both sides a handful of times with hard pressure, followed by a handful of times with lighter pressure. I wiped it clean and that was that! The edge was sharp!

He got so excited when I handed his sharp knife back to him, that he wanted to see this sharpener right away! And, now, I have to wrap up this writing, because he wants me to go sharpen more of his knives.

FIELD NOTES / 02

HE LOVED ARCHERY

By Andri Elko

When I was a kid, I dog-eared a Bear Archery Kodiak Cub recurve in the Cabela’s catalog. I saved my pennies to buy it myself. I never really had an allowance, but I took babysitting jobs when I could. My friend Chelsea and I painted rocks and walked around town trying to sell those to people we passed by. We also made and sold friendship bracelets and lemonade.

I look back on those early years and smile at our youthful entrepreneurial spirit. But mostly, I smile because there are people in our community who were kind enough to buy rocks from kids; and supportive enough to shell out hard-earned money for a Dixie cup of lemonade. Chelsea and I, joyfully oblivious to our surroundings, sold that lemonade out of a ramshackle weathered-wood stand we set up right next to a husky’s old dog house. The memory in my mind is a quaint and quintessential picture, but, in all honest likelihood, the reality of that dog yard was probably not so quaint and not so quintessential. Lol.

I still have that Kodiak Cub. I plinked with it on the beach in front of our house for summers on end as a kid. I ripped DuctTape into X’s for target-marks on cardboard boxes. With that little bow, one or two good-sized rocks set inside a box was enough to weigh it down. If I shot well, I’d peel off the X’s and bring them in to show my Dad. For years — like maybe 10+ years — one of those “good X’s” was stuck onto the cover of his address book that he kept in the corner shelf near the kitchen. It’s interesting, the little things life chooses to keep around.

My next bow was a Jennings Star compound bow. I still remember the day it arrived at our home in a large homemade wooden case. I anticipated that bow with such deep and barely containable excitement! This compound bow was a BIG deal! It was also the first time I ever negotiated a trade of any magnitude.

His name was George P. Mann, a bowhunter from Alabama. He was visiting us in Unalakleet for a grizzly hunt that he had booked with my Dad. I was 11 or 12 years old at that time. My swarm of curiosities and questions about bows and archery were met with such patience and kindness from Mr. Mann.

Before he left Alaska (after a successful bowhunt) he made me an offer. The deal was this: First, I would tie 100 Egg-Sucking Leech fly-fishing flies and send them to him. Then, he would send me a compound bow set-up. Honestly, a place remains in my heart that still — still —can’t believe it.

I spent the next few weeks in my bedroom covered in fuchsia chenille fibers. My fingers dyed purple from marabou. Gosh, I cringe looking back, thinking how pathetic those flies must have been. I was just a kid, of course I thought they looked absolutely incredible, but now I’m old enough to know better.

It’s only in hindsight that I now see the legacy in Mr. Mann’s gift. He didn’t make that trade because he needed flies to fish with. He didn’t give that bow to me simply because I wanted a bow. No. He gave that bow to me because he loved archery.

By giving a kid a bow, and making me work for it and value it — he was planting seeds and cultivating the next generation. By this, I mean both the next generation in terms of my own sense of value and pride in accomplishment and also in terms of the next generation of archery.

George P. Mann is a legend. He is. He lived and breathed bowhunting and conservation. He shared it as naturally and freely as air. His enduring legacy is beyond any person or comprehension, really. All I know is that his love of archery is reflected in my own love of archery. And I know, for certain, that my life would be unimaginably different, void in an unknowable yet perceptible way, had he not been a part of it.

When I outgrew that Jennings that he gave me, I gave it to another young girl in our village. It was never really mine anyway. It was a seed, a seed that grew and dispersed — like dandelion swept up by a gust of wind.

I’ve had other bows since, some traditional and some compound. I’m not a purist when it comes to traditional archery — but I do prefer it. Just like I prefer swinging dry-flies for grayling, but I also slug out blaze-orange Pixies and chartreuse Vibrax when I want to limit out on salmon and fill the freezer. And there’s the newer magic lure, the Flying-C (my now not-so-secret secret weapon.)

Subsequently, as I write this it has me thinking back…

Mr. Mann is also who taught me how to cast a fly-rod and fly-fish. He offered his rod for me to use, gave me casting advice, and let me have-at-it as long as I wanted. I remember standing there near sundown on the edge of the dock, surrounded by the sound of crickets and warm southern air, practicing my cast on the Alabama catfish pond.

I think there’s room and reason for all ways, and a well-suited way for the right occasion. And, if we’re lucky, we’re blessed with people who teach us the right way along the way. Our world is made by what we make of it.

Perhaps one simple crux this story has to offer is this: Gifts and choices alike, are enriched not so much by their what, but by their why. And their true value, the kind that endures, is imbued by the giver of the gift and by the person behind every choice. It’s people that matter most.

Read about Mann Wildlife Learning Museum here: https://www.montgomeryzoo.com/mann-museum/the-mann-museum

FIELD NOTES / 01

IT’S CALLED BREAKUP

By Andri Elko

Today I pulled a treasure out from safekeeping. Its black matte glass felt smooth and flawless as I ran my hand along the upper limb toward the riser swell. My hand grasped the grip’s light bourbon leather wrap, and it felt like an old familiar handshake. My fingertips traced along its seam of baseball stitching that my friend sewed so perfectly years ago now.

He’s passed away since. Still, the marks of his life on earth live on in the bows that he made and in the memories of the lives that he touched.

Handmade hunting tools are priceless. Wooden bows and home forged knives are my favorites. Heart and soul are poured into their making, etched into every angle and edge and underlying every choice of material. There is history in the methods used, some that stretch further back into time than others. Some even reaching back far enough to beckon forth the whispers of ancestors who call us deeper into our shared human story.

It is from those internal borderlands between the human self and the higher soul, where the unseeable and untouchable breeze of Spirit gently fans the flames of our eternal fire. Hunting, in its own and ancient way, conjures the proverbial act of setting out the stones and placing the kindling to be lit. It is a way to prepare and sit before that sacred fire, to wait, to witness, to partake. It’s that fire that gives meaning to experience and purpose to our presence. It’s that fire that feeds the soul of a hunter; that fire that warms us in this earthly cold; that fire that lets us know we are here for a breathly moment. It’s that fire that reminds us that all life — our life—is a fleeting gift tied to the passing of time and enfolded with layers of story.

A flemish-twist, a cedar arrow, a wooden bow. We may purchase these, but their value is so much more than their price. They carry the fingerprint of natural life and of un-urban legends. Within their grains and fibers waits a quiet longing, one that yearns for companionship. In that way, they are like us. These homemade tools invite us. They desire to enter into seasons, backwoods, valleys and mountaintops. They, in a way, become a part of us, helping us to fulfill who we are meant to be.

This longbow is a 61" Osprey of Holm-Made bows made by Chad Holm. Chad gave it to me after teaching me to build my own longbow over a weekend of backyard shop-time and Badlands shooting-time with Chad and his son and our friend Brad Davis. Brad introduced us and invited us all together to build bows and shoot for a few days. Brad helped me build my first bow, a recurve. Chad helped me build a longbow in Brad’s shop.

I will forever be grateful to the generosity of these two incredible men for their willingness to share their knowledge and for the gift of their valuable time. God crossed our paths and used traditional archery to do it — and it has enriched my life in all good and beautiful ways. They’ve become legends in my own tradbow story, giants who lifted me simply to share the wonder of their view.

In Bush Alaska now, it’s that in-between season. That stretch of Spring where the river ice is too thin to travel and bound by the river’s banks and borders. Our sea ice is almost a memory, some still clings to the coastal shores. It’s covered with glistening greenish-blue overflow and darkened “shadows” of water waiting just below. Seals lie beneath the sun, sleeping like oversized slugs. The loud cries of hungry seagulls shout the arrival of Spring. And the skies offer a welcomed return for birds migrating back to these lakes, muskeg, tundra tussocks and rocky cliff crevices of their birth.

This is the shortest season, but it feels like the longest — it’s called Breakup. It bridges winter-spring with summer-spring. It’s a time for preparing. It’s full of anticipation. It’s a time for gathering up treasures like this longbow. I string it, set the brace height, wax the flemish string and attach the quiver. I pull out my wooden arrows and sharpen broadheads. I wait, shoot and tune my tools and myself to what is true. The clock and clutter of urban life fades like sea ice swept into the horizon by unseen winds and currents. Time passes. Story unfolds.