FIELD NOTES / 05

20 FEET CLOSER TO GOD - Extended Version

(Shortened version published in Traditional Bowhunter [Feb/Mar 20.])

By Andri Elko

Photo by Chris Chastain.

“When a hunter is in a tree stand with high moral values and with the proper hunting ethics and richer for the experience, that hunter is 20 feet closer to God.” — Fred Bear

The simple and subtle qualities of traditional archery allow us to enter the unknown lightly, quietly, and humbly. Our accuracy is reliant on discipline alone. Our ability is honed through repetition and the practice of discernment. Ideally, with every full-draw, we are drawn deeper into ourselves.

Every instinctive archer understands this. We don’t think about when to release an arrow, it just happens when everything feels in alignment. And if you touch upon that alignment with truth when you release the arrow, then there is an alignment with truth in where the arrow finds center. Our guidance rises from a foundry deeper than that of thought. Like a compass, each decision and every response operates under the influence of unseen forces. At that ancient precipice that precedes a loosed arrow, we connect to a place that can only be understood through direct experience; and it feels like a sacred place.

—

Traditional archery invites you closer. It involves a kind of intimacy that has been slowly eroding beneath waves of hunting technology and long-range tactics. Bowhunters learn to tread the earth more lightly. We hunt for experiences, not for exchanges. We tap into subtle degrees of awareness; we practice the art of patience, we let go of expectation, and we refrain from getting in our own way. Our hunt becomes a kind of communion, an interplay between the earth and our short walk upon it — a conversation between our better selves and that which is always learning and growing. Traditional archery is timeless. And all that is timeless can also be a catalyst toward the deep eternity within our souls, and it is there that we begin to truly know ourselves.

After a lifetime of rifle hunting, and a bit of compound time, I felt a deeply seated desire to simplify, to rely less on commercial gear and more on my own instinctive ability. I wanted to get up close and personal; both literally and figuratively; both with the outer wilderness and with the wilderness within.

So, I decided to build a bow.

—

I called the nearest bowyer. With a guarded response, he said that he couldn’t show me his workshop or share any of his bowyer know-how because it was his livelihood. I understood that inclination, but I also believe that when we don’t share knowledge and art, we all lose. Traditions and traditional knowledge are inherently meant to be shared and passed on. This is part of traditional archery’s ancient beauty; and this is precisely why we are able to partake in that beauty today.

Thankfully, as fate would have it, I found a local bowyer though TradGang. Brad’s generosity in teaching me what he knows about traditional archery has been a blessing in my life; as has his friendship. I’ve learned as much about bowery and traditional archery as I have about attitude, character and values that truly endure all things. I’ve been welcomed into a community of archery hunters; a community that is rich with experience and wisdom gained through years of trial, error, and grit. We’ve shared stories, shared knowledge, shared hot-wings and beer. We’ve shared the joys of our successes. We’ve also shared the swell of encouragement that fills up the wide stretch between every peak of success.

Our traditional hunting community is much like a bow. Alone, a bow is just a piece of wood. Its purpose is limited without its relationship to the tight string, the arrow, the aim, and the archer. Without the relationships we cultivate, we too are alone and limited. I’ve learned that the traditional community is a tight community that can bring people together, achieve shared aims and purposes, and encourage us to participate collectively while also allowing a reserved place for our individuality. The traditional bowhunting community feels like a treasure unearthed; and in finding it, I’ve also found a part of myself.

As hunters, it seems that our choice of weapon mirrors aspects of who we are. As we distill and simplify, we lessen the weight and clutter, which in turn gains us a clearer glimpse of our identity within this human experience.

What does it mean to be a hunter?

What does it mean to be a good hunter?

Ultimately it is not a bow or rifle that makes someone a good hunter. It’s not the gear or number of years put in. It’s the heart that makes us hunters. When our hearts are in alignment; the aim will be true.

This is what I’ve learned from my experiences, from family, from Brad, from other bowhunters, from time in a tree that lifts me 20 feet closer to God. I am forever grateful to the people who have accompanied me along this seeker’s path. That’s the thing about uncovering truths: when they’re unwrapped, they can be applied to all of life. In this way, traditional archery has evolved from an activity and a pursuit into a kind of philosophy, a lens through which to see the world in which we live.

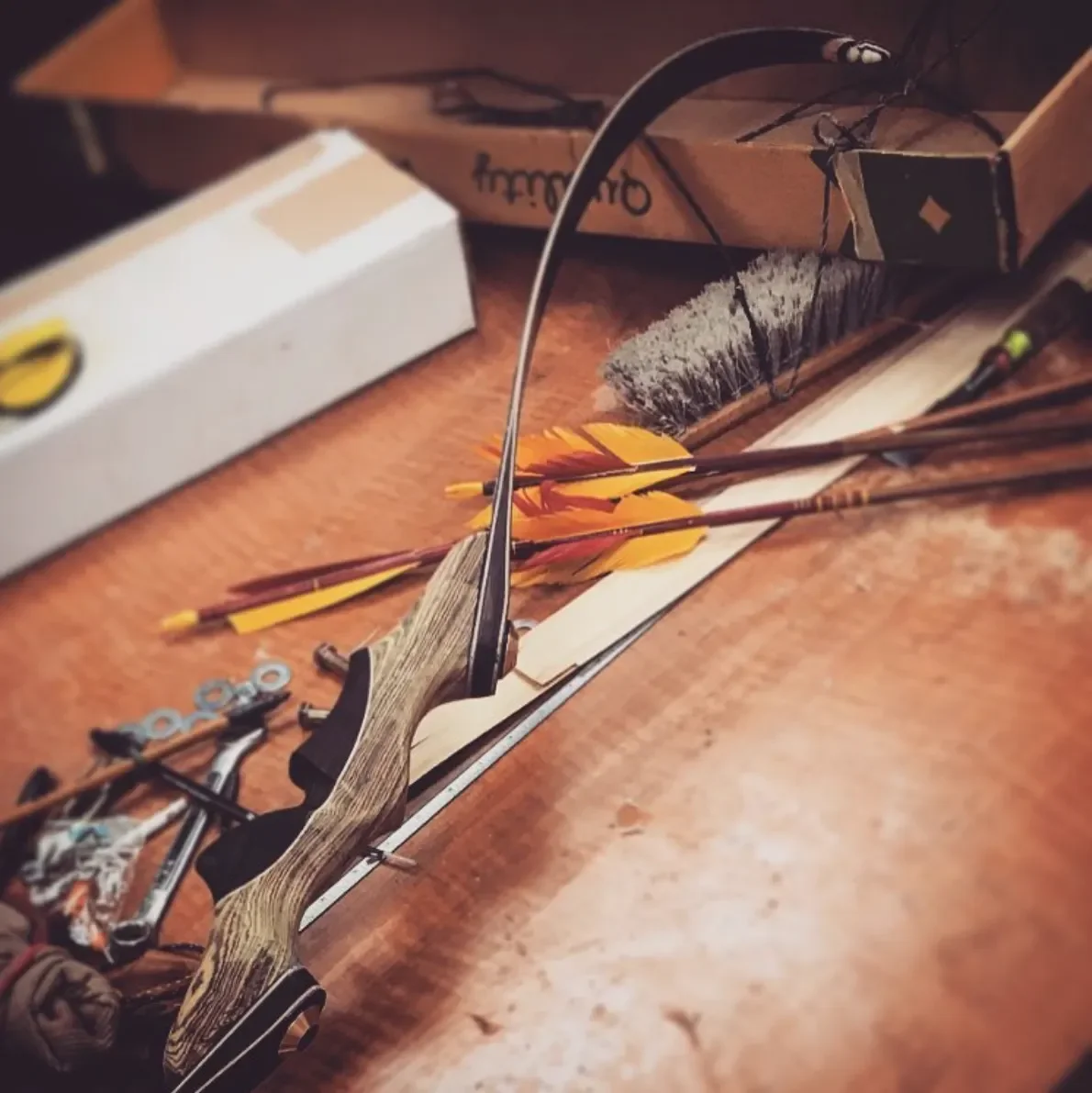

My first self-made bow, pictured just prior to the last stage of a finish application. It’s a take-down recurve with an ebony/bacote riser, maple accents and black fiber-glass limbs. Photo by Andri Elko.

—

The first bow that Brad and I built together was a three-piece take-down recurve. I love that bow. It’s beautiful. Hours were spent in the shop and at the sander. We wanted to make it as minimal as possible without compromising strength and function. If we didn’t need any material in a particular area, we sanded it away. Bare minimum was our motto. The result was elegant, simple and inviting.

I could never have dreamed up a better first bow. It came in a bit under our target draw-weight, but it’s lovely in the grip and makes for a smooth shooting small-game and target bow. Having made it, having watched it come to life, I can see how the qualities that have been poured into making that bow now accompany me everywhere I carry it. It holds good vibes of friendship; it keeps alive the memories of shared knowledge and determined efforts; and it reflects the gratitude that grew with it and continues to grow with every draw of its twisted string. Even when I go out alone, with that first self-made bow in my hands, it feels like I have an old friend by my side.

A few months (and a few bows) later, Brad introduced me to his buddy Chad, of Holm-Made Traditional Bows. Brad, Chad, Chad’s son and I played wack-a-mole in the prairie dog fields during daylight hours. In the evenings, the guys helped me build a longbow in Brad’s shop.

I found pecky pecan veneers that looked stunning under glass. We stacked contrast accent wood on the belly and back of the riser; creating a look that is almost topographical in how the layers accentuate the contours of the bow.

At a 40-plus pound draw-weight, this is the bow I took to the woods that fall. It’s light and quiet. It practically disappears into Dakota’s golden prairie grass. Someday I want to nock it with flu-flus and go after pheasants. But for now, it’s set up for deer. I strapped a Selway quiver on the limbs and filled it with the cedar arrows that Chad had so generously sent me from the Footed Shaft.

To me, hunting is 5% opportunity, 5% skill, and 90% relationships. The success of one person is always, to some greater or lesser degree, a shared success. Relationships craft and cultivate our perceptions, fortitude, ethics, and our memories. We learn from Nature and from one another. What we take away from our experiences becomes part of the story we leave behind.

Stretching a flemish-twist string with Alaskan beaver-fur silencers. Photo by Andri Elko.

Chad Holm teaching Andri how to make a longbow. Photo by Brad Davis.

Cedar shafts and turkey feather fletchings. Photo by Andri Elko.

—

I set my goals.

I fortified my foundation.

I built my longbow.

Now, it was time to buy tags and take to the woods.

One brisk fall morning Brad took our friend Natashia and me to his stands in the Badlands. We scurried through a field, crossed a shallow river, and climbed up into the trees. I settled in just as first-light began to crawl across the ancient strata of a land that’s been hunted since the dawn of time.

I liked this setup. The old juniper wrapped around me. I felt like an owl sunken into a hollow; and like an owl, there I sat, camouflaged into a grayish-brown background of bark.

In the last 10 minutes of my sit, a large doe emerged out of the foreground. She came forward like a wisp of smoke. Silently, she walked into a widened corridor about 15 yards from the stand. I drew 3/4 of my full draw, my mind turning back and forth about the shot, and then I let down.

I wrestled with the idea of shooting this doe because I had set my heart on a buck. It was a clear shot, but something I can’t quite articulate kept me from taking the shot.

She tip-toed in a little closer. She stood broadside. She turned her head and stared back into the timber. Her right front leg extended out in front of her, and I could see that tuft of snow-white fur beneath her armpit. It was almost like she was inviting me to shoot, waiting on me. I drew back again, held for a second and let back down.

Everything was picture-perfect for a clean shot. Externally, all signs were a “go,” but everything inside me said, “Wait…wait…this isn’t the right deer, this isn’t the right moment.” As much as my practical mind rationalized this excellent opportunity, I could not ignore what I was hearing within. I knew that if I let that arrow loose, I would be doing it for the sole purpose of shooting a deer. This would have been fine if it were how I had set out from the start. But, it would have been a betrayal to myself if I had not listened to that inner guidance. After all, this is why I set forth down this traditional path in the first place — to tap into that something deeper.

—

My Dad’s friend, Chip, let us hunt near a North Dakota river bottom. It was nice to be in the woods with my Dad again. We set up in a ground blind as darkness quietly lifted. The land was alit with that old familiar cold-blue hue. Deer criss-crossed through the trees in the distance, but no bucks came within bow-range.

For the evening sit, Dad and Chip and I thought it would be best to go sit in the treestand. They dropped me off at the stand and went back to camp to wait. This was my last sit of the season, and we all were keeping our hopes high.

I’d been up the tree for several hours without a deer in sight. The sun was sinking now, and I knew there was only an hour or so of shooting light left. I was starting to feel the chill so I did some slow deep breaths and imagined my body warming up with every exhale. Hunting, as so many of us know, is often a challenging exercise in mind over matter.

Then, in a blink, things started to change.

A doe and her two young ones walked beneath my tree, following one another along their heavy trodden path from the timber line. They lingered under the shadow of my tree for a while. Then a buck sauntered in, circling the doe below. He had only one antler left. It was broken off into a ragged spike. I mentally hemmed and hawed about that buck, thinking,“This is a buck after all, and this is the last hour of my season.” But still there was that inner voice telling me to wait. Let me clarify here that I was not being choosy, although to some it may seem that way.

I was listening in.

I entered that sacred space.

I waited.

Then, minutes before the ember of last-light began to fade, the magic began to stir…

Hearing the crunch of hoofed-steps in the snow behind me, I stilled myself, slowly peered over my right shoulder, and saw a mess of antler directly below me. I counted up to five points and quit counting. I quit looking at the antlers all together. In a flash and without a doubt, I knew that this was a great buck, and one that far exceeded any hopes I might have had.

Maybe 20 minutes of shooting light remained now. The doe and her two fawns were still out in front of me. This buck stopped 12-yards out and quartered away a little. I drew back, but one of the young ones spotted me and spooked, which caused the buck to spook too. He shuffled a little, and his eyes seemed to grow in size. I let down a little and froze.

Time stretched.

The deer grew calm and comfortable again and scattered around my tree. This was difficult to contend with, because no matter how you draw back, the odds are that at least one eye is going to catch your slightest movement. The buck was still in the 10–12-yard range. He nosed the ground there, maybe catching wind of doe scent.

I pulled back on my string, and at partial draw the buck grew suspicious again. I froze. Then the buck turned his head just enough for an antler to cover his right eye, and there it was: the window.

It is in those seconds that stretch time — when too much time can miss the opportunity altogether and too little time can ruin the opportunity by rushing it — that we find ourselves at a threshold that leads us into something deeper. For some of us, our minds quickly make the decision for us. But there are those of us who listen in and enter. From this threshold it feels as though some force — both beyond us and at once within us — takes the helm. We watch things unfold naturally, in the same harmony and balance shared by all other forms of Nature that unfold in sync with their primordial pace and rhythm.

I finished into a full draw, anchored, and that arrow took flight like it knew where it was going. I watched the feathered fletchings indicate a solid shot. The buck spun and bolted. I can still picture him leaping in the air with my fletchings barely sticking out of his right side. I didn’t get visible full penetration of the arrow, but it must have been partially through the other side because the deer’s movement worked the arrow through and through, and I never recovered it.

The shot-angle was ideal.

Both lungs were hit; it was clean and lethal.

Practice shots 20 feet up. Photo by Chip Erickson.

North Dakota whitetail. Longbow. 2018. Photo by Vance Grishkowsky.

North Dakota whitetail. Longbow. 2018. Photo by Vance Grishkowsky.

—

A hunt can often be distilled into one vital moment. But that moment is never truly lived without first giving it the time that it calls for. Time, as such, becomes a quiet teacher. There are things in life that cannot be rushed; things that swallow up time and nourish us with an accumulation of gifted moments. We fill ourselves with these fleeting gifts which feed a hunger, a yearning, within us. Every moment becomes a bread crumb leading us closer to, and further into, that something deeper we all seek, whether we are aware of it or not. As we dwell in those depths, we begin to understand what timelessness truly entails.

Outwardly, I am gifted with a beautiful harvest: clean wild food in the freezer and an exceptional memory of shared experience.

Inwardly, I am fulfilled in ways perhaps only revealed to those who tread the wild unknown. We wait in the cold brittle air of a late fall season. We struggle in our quest to cast out any excess of thought that clutters up an expectant mind. We reach inward for that ancient alignment, trying to find our way into the depths of that timeless space. To touch upon that timelessness just once, is to touch upon it forever.

We sit there alone in the stillness and the silence. Some part of us clings to a primal human memory, one that remains safeguarded in the vault we each carry within. We cannot force our way into that vault; only stillness, silence and surrender can show us the way in.

And even when we appear to stand alone; even when the judgements of others isolate our actions — still, we all together share that upwelling sense of gratitude that visits in moments of blessed unfolding.

Just as we admire a fiery sunset, so too, can we appreciate a clean and pure hunt. To know, in that deep inner reservoir, that all life lives on, unbound by time and earthly form. We find our way into a sacred connection, one that unveils and hones the edge of our ability to discern that great yet subtle difference between taking and receiving.

To date, I’ve only harvested this one big game animal with a traditional bow setup. In terms of tags and years, I can’t claim to be an expert to any reasonable degree. But traditional archery seems to me to be a qualitative venture, not a quantitative one — one that truly does lift us 20 feet closer to God.

What I felt with one well-placed arrow is perhaps the truest aim of today’s take on traditional archery. And for the gift of that moment — for that flicker of pure immersion into the ephemeral borderlands of our human experience — I am grateful.

“The history of the bow and arrow is the history of mankind.” — Fred Bear

“All America lies at the end of the wilderness road, and our past is not a dead past, but still lives in us. Our forefathers had civilization inside themselves, the wild outside. We live in the civilization they created, but within us the wilderness still lingers. What they dreamed, we live, and what they lived, we dream.” — Thomas K. Whipple